The Ozark Plateau sweeps across the northwestern part of Arkansas, bringing with it the beautiful oak-hickory forests and striking bluffs that earned Arkansas the title “The Natural State." Among these old limestone remnants are innumerable deer, lumbering bears, and a variety of lush plants taking advantage of prime habitat in this premiere natural beauty.

One such plant, a small shrub found on rocky bluffs and hillsides, was all but lost: the Ozark chinquapin. Arkansas State Parks’ mission makes conservation of natural resources a top priority. The Ozark chinquapin is no exception, and several Arkansas State Parks have come together to help save this species.

Once a forgotten piece of Arkansas’s heritage struggling for survival, the Ozark chinquapin species is now well on its way to recovery with the help of Arkansas State Parks. Read on to discover more about this project.

Part of its struggle for survival came from the chinquapin’s wood being highly sought after. This scrubby plant was once a dominant tree species and prized by settlers. The wood was a wonderful mix of workable and durable. And most importantly, the wood was known to be highly resistant to decay. These qualities made it a prime candidate for harvesting to make many outdoor implements and fence posts.

The other reason that chinquapins were so highly prized was for their edible nuts. A member of the chestnut family, these nuts made for a tasty treat sought after by Arkansans and wildlife alike. The nuts would be found in a spiny bur of a shell casing, making getting inside tricky business at times. The end result is well worth it. Those lucky enough to find a nut remark on the wonderful flavor.

Ozark chinquapin nuts grow in a spiky bur. Come September, the seed ripens and the bur opens up, dropping the nut to the forest floor.

Like other North American chestnuts, the species was almost entirely wiped out by a blight that reduced the population from towering trees to the undergrowth we see today. The Ozark chinquapin found itself targeted by a specific type of fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica. More commonly known as the chestnut blight, this disease still affects the species to this day. Once a chinquapin’s trunk gets large enough, the fungus finds a home there. The fungus kills the inner bark layers, causing swelling, and opening the tree to infection. In most cases, this kills the main trunk of the tree, causing young shoots, or suckers, to grow around the dead stump, creating the shrub shape that we now recognize.

The blight fungus forms a large swelling in the trunk called a canker. These cankers continue to grow on the trunk of the tree until the trunk dies. The main trunk shows an advanced canker, with a smaller canker present on the right stem as well. The orange crust on the smaller suckers here is also the work of chestnut blight. Two years ago, this was a healthy tree.

A few individuals managed to evade the blight. Some trees were isolated from the rest of the population and were able to avoid infection. Even fewer trees were naturally resistant to the blight.

Despite struggles, the clusters of blighted individuals still cling to hillsides, producing small amounts of burs and nuts, but unable to grow tall main trunks due to the blight. These survivors can even be found in a number of Arkansas State Parks! One such place is Mount Magazine State Park in west-central Arkansas. Chinquapins found shelter in the geographic isolation of the state’s highest point. The bluff lines there harbor over a hundred chinquapins. Though many are blighted, quite a few still produce large burs with seeds. The best part of this remote population is the presence of several large unblighted trees. They share little to no looks with their shrub-like siblings and instead stand as tall as the original hallmarks of the species. One such tree was discovered in 2019 and found to be the largest documented chinquapin in Arkansas.

The Arkansas champion tree for the chinquapin was discovered in 2019 and soon registered by staff at Mount Magazine State Park. The Arkansas Forestry Commission keeps records of the largest trees found in the state and their locations. Feel free to visit the ones found on public lands or even to submit your own champion if you have discovered a larger tree. The champion chinquapin’s location is kept relatively secret, the more exposure to the public, the higher chance it will catch blight.

This champion serves as a reminder of what was lost, an entire species of the Arkansas canopy. Mount Magazine is not alone; other state parks also have special stories related to this species, finding secluded specimens throughout the Ozark plateau. One park went so far as to help jumpstart a nationwide recovery effort.

Hobbs State Park-Conservation Area Takes an Interest

Arkansas State Parks first became part of the recovery effort at Hobbs State Park-Conservation Area in northwest Arkansas near Rogers. The year 2002 brought a surprise to the staff at Hobbs. Al Knox, the park’s trail maintenance supervisor, was weed-eating one day at the Van Winkle historic site when suddenly he was face to face with a spiny tree growth that he had not seen in 50 years - not since he was a 10-year-old kid from Bentonville. It was a seed bur on an Ozark chinquapin tree! Taking a better look, the tree was absolutely loaded with seed burs. Al was quick to spread the word to the other staff. Now what was the best thing to do with this find?

In searching “Ozark chinquapin” on the Internet, the staff discovered there was an organization established trying to save the tree, the Ozark Chinquapin Foundation (OCF). The OCF wanted to start test plots in Missouri and needed the best seeds they could find. At the time, the Hobbs tree was high on the list. For several years the Hobbs staff collected all the Ozark chinquapin burs that were obtainable and sent them to the OCF for their research.

The Hobbs staff was then requested to get more actively involved. Steve Bost, the founder of the OCF, asked if the park would like to try some cross-pollination with the good Ozark chinquapin. No one had ever been successful cross-pollinating with Ozark chinquapins, and knowing absolutely nothing about what they were doing, they said, “Sure."

Hobbs staff were given frozen pollen from four of the best Ozark chinquapins known at the time. That pollen came from trees in Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, and Mississippi. The staff crossed their fingers that they would have some success. Dr. Fred Paillet from the University of Arkansas said the experiment would be a success if just one seed came from the cross-pollination. Outside expectations for the experiment were not high.

Timing was everything, and their guesses as to when to hand pollinate and bag the female blooms proved to be lucky ones. They included “test” bags where they bagged other female blooms but did not hand pollinate them. If seed developed in the test bags, local pollen would have been involved, ruining the experiment. No seed came from those bags.

Pictured here, Hobbs Park Interpreter Steve Chyrchel poses with the test chinquapin trees after placing paper bags on top of the pollinated blooms to separate the flowers from local pollen and maintain a controlled experiment.

Speaking of bags, this was a key factor. The team at Hobbs used white paper bags that were left over from a special event where they put sand and a candle in them to light a path at night. Others who had tried cross-pollinating Ozark chinquapins apparently used waxed or plastic bags. Well, what’s going to happen with waxed or plastic bags? The tree is going to respire, putting water in the bag. If the water can’t escape, everything in the bag rots. By using paper bags, any water coming from the tree soaked through the bag and evaporated, saving the pollinated blooms. Too simple! When all chance of local pollination passed, the seams on the paper bags came unglued exposing the seed to sunshine. Eureka! Hobbs ended up with 32 viable seeds and were the first ones ever to be successful hand-pollinating Ozark chinquapin trees.

Hobbs staff gave all 32 seeds to the Ozark Chinquapin Foundation, and they were planted in plots in Missouri. One of those seeds from Arkansas pollen was the only one to survive. What has resulted is amazing. That tree was only eight years old last fall when it produced over 2,700 seeds! When you cross-pollinate with good genetics, you get even better genetics and a more blight-resistant tree.

The next step for Hobbs State Park was a test plot of their own. In 2014, park staff, Benton County Master Gardeners, and students from Northwest Arkansas Community College, planted 52 Ozark chinquapin seeds at an ideal location: well-drained, south-facing slope, rocky soil, and full sun. In 2019 about half of those trees began producing burs for the first time.

Success Leads to Other State Park Ventures

Lake Dardanelle State Park, located in the Arkansas River valley at Russellville, joined the recovery effort to save the Ozark chinquapin just as the trees growing at Hobbs State Park-Conservation Area were beginning to produce seeds. After planning and coordinating with the OCF and Hobbs staff, Lake Dardanelle staff planted a test plot in March of 2019. Ten plantings were done using seeds produced by trees that have shown greater resistance to the blight than the Chinese chestnut, which is considered resistant to the fungus.

These trees and their seeds are the future of the species. Each seed was planted and then protected by placing a grow tube around it. Wildlife love to nibble away at young trees—not just the seeds—so each tube gives its tree a fighting chance to establish itself. Two of the ten plantings did not survive the first growing season, and an additional tree did not come back after the winter, leaving Lake Dardanelle with a 70% survival rate. Plans are in the works to plant additional seeds in the plot.

Pictured here, Lake Dardanelle State Park Interpreter Megan Ayres and OCF members plant an Ozark chinquapin seed in the Lake Dardanelle test plot.

The ultimate goal is to restore the Ozark chinquapin to its native range by taking advantage of the natural resistance found in the rare, healthy specimens scattered throughout the Ozarks. It has proven it can grow in the original plots, but how will it fare elsewhere? Partners, such as Lake Dardanelle State Park, who join the effort are provided seeds. These test plots help measure how well the tree is growing and adapting in different areas outside of the original test plots. Those original plots build the foundation of the restoration effort, but new plots are necessary for the tree to have a chance to ever re-establish itself in the forests.

Where the Chinquapin is Now?

A largely forgotten tree after the chestnut blight swept through in the mid-1900s, the recovery of the Ozark chinquapin is a story that is more than any one park by itself. Instead, there is an army of people dedicated to seeing this become a success story.

Visit Mount Magazine, Hobbs, or Lake Dardanelle State Parks to attend a program led by park interpreters to learn more about this tree. Scheduled programs can be found on the Arkansas State Parks website. Some plots are open to volunteer community involvement in recording data and observations on the growth of the trees, as well. You can also learn more about the multi-state recovery effort being championed by the Ozark Chinquapin Foundation.

Ozark chinquapins, a forgotten piece of Arkansas’s heritage once struggling for survival, are now well on their way to recovery with the help of Arkansas State Parks.

Sources / For further reading:

Ozarkchinquapinmembership.org/breeding-program/

|

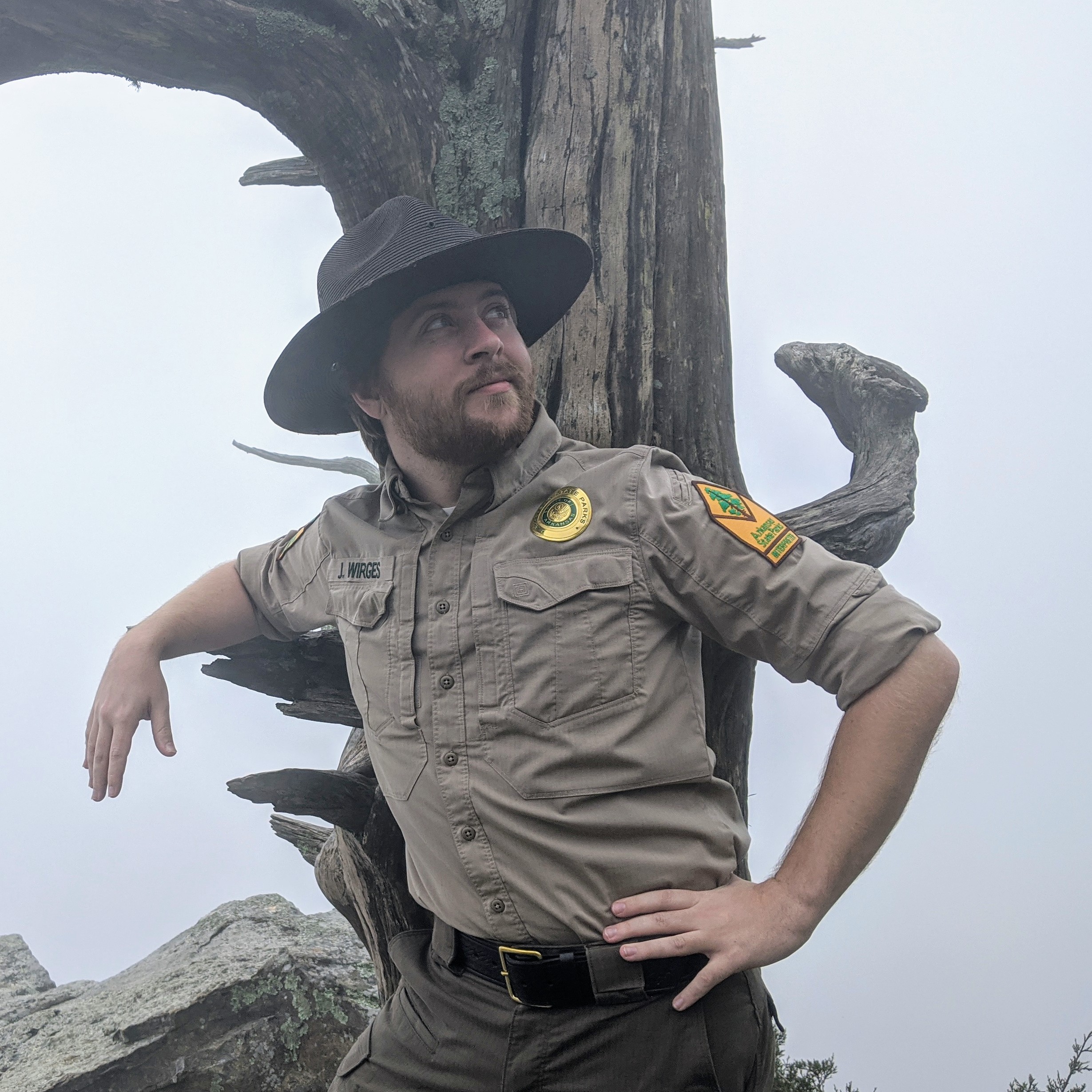

Jonathan Wirges joined Arkansas State Parks as an interpreter in the spring of 2015. He is currently stationed at Mount Magazine State Park, enjoying the many trails and diverse wildlife that call the park home. He grew up visiting parks throughout the state, and relishes the opportunity to introduce others to the best parts of the Natural State. Jonathan spends most of his free time reading, sketching, and doing puzzles with his friends and family. |

|---|---|

|

Steve Chyrchel ran his own tourism business for 30 years. He later joined Arkansas State Parks as an interpreter at Hobbs in 1997. He has been the driving force behind Hobbs’ chinquapin plot and is an active member of the Ozark Chinquapin Foundation |

|

Megan Ayres is a park interpreter at Lake Dardanelle State Park. Some of her favorite pastimes include being outdoors, cheering on her favorite sports teams, playing trivia, and doing puzzles with her friends and family. |