Intimacy of candlelight

By: Chris AdamsLighting in the 19th century brought families closer together in the domestic space, creating an intimacy that today's electric-driven lighting cannot replicate. This is the theme of our new mini candle-making workshop. Historic Washington State Park’s interpretation focuses on what makes candle illumination unique, the technological improvements in lighting and how it relates to Washington.

The theme that 19th-century lighting brings families closer is not an idle statement. Think about the present. When a family walks in the house at night and flips the light switch, what do many family members do? Do they sit and enjoy each other's company? Or does each family member walk to their favorite spot and continue with their solitary interests? To say that artificial illumination is perhaps one of the most significant advancements in human history is not an understatement. It allows us to do work, leisure, or other activities we enjoy well after the workday ends. However, we tend to lose something in return with each successful attempt to improve over previous designs.

Today, we can light up entire houses, buildings, stadiums and cities, but people did not try to illuminate whole rooms before lighting from electricity. Instead, the goal was to have just enough light to do a specific task. So, instead of lighting an entire room with each person going their separate way, the soft glow of the light emitted by the candle brought friends and family members closer together so they could share the light and talk to one another, read books, knit or play games. It is in this framework that the candle created so much value.

Another aspect the program focuses on is the candle and early lighting technological advancements. These advancements primarily center on the candle's composition, such as tallow, beeswax, spermaceti, stearin, and after discovering oil in 1858, paraffin and kerosene. These different compositions created a fuel source that each had advantages over the previous.

Tallow candles could be made at home, or a person could buy them cheaply. If making their own candles, they could dip them or make them from candle molds. There are several candle molds found in the household inventories of Hempstead County residents in the the1840s. The advantage of using the candle molds was that more candles could be made at one time, plus the finished product was straighter. However, the easiest way was to dip the candles.

Special care must be taken with tallow candles. Tallow has a lower melting temperature than the other types of candles, so they warp easier in warmer weather, and storage was vital since they were animal fat, and fat attracts vermin. An ancillary use was if a pioneer or traveler was in a pinch and found himself without food, he could always eat his candle. It may not be too tasty, but it would keep you alive for a time.

Beeswax was superior to tallow in that it was more durable, burned longer, brighter and did not draw insects. However, beeswax candles were expensive. This kept them from being used extensively. When perusing through the inventories of the 1830s and 40s, many county residents cultivated beehives. The conclusion can be drawn that some residents made their candles from the hives they cultivated on their property.

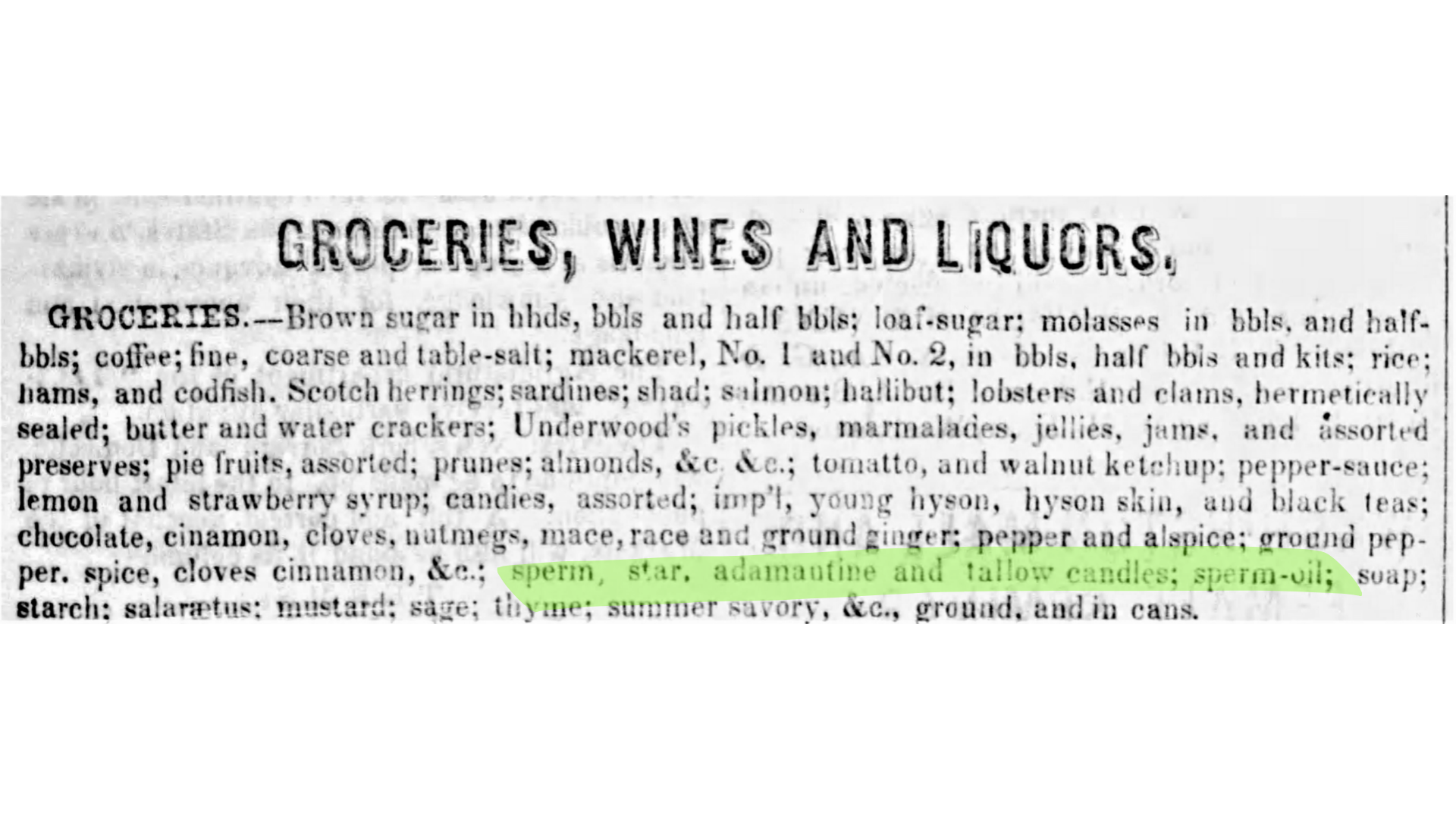

Spermaceti is another popular lighting source found in the home of the county's residents. Spermaceti is taken from the head of the sperm whale. Obviously, it was not produced locally but procured for Hempstead County residents from New Orleans via the merchants of Washington. Benjamin Britt and Abraham Block are two such merchants supplying materials from New Orleans. This Britten Ad (Washington Telegraph Dec. 13, 1848) highlights the candles sold in his store near the bottom.

Whale oil was another type of fuel from the whale. It was the most widely used until 1859 with the discovery of petroleum oil. This type of oil came from the blubber of the Greenland Right Whale. It was cheaper than Sperm oil; therefore, whale oil was the preferred illuminating oil. We have whale oil lamps on display in several of our tour homes in Washington like the one below in the Royston Town House.

The most popular candle of the period was the stearin candle which became synonymous with the "star" candles made by Procter and Gamble. The term "star" came into common usage due to the Proctor and Gamble company logo used in the 1800s that is pictured below. Stearin is derived from tallow and is separated during a chemical process called saponification. This chemical separation cannot be done at home, so people procured these candles in stores. Stearin candles maintain their shape better than tallow. Also, stearin, beeswax, and spermaceti have less smoke than tallow and burn longer. Therefore, stearin was the better alternative to the more expensive beeswax and spermaceti candles and of better quality than the cheaper candles made of tallow.

Probably the most significant advancement to the candle was not the composition of the candle but the plaited wick. This could be thought of as trivial today because of its simplicity, but it was truly innovative in the past. When a rolled wick is lit on a candle and burns, the wick's end becomes charred. This charring is snuffed (trimmed) so the candle would have a steady flame. If not, the flame would eventually extinguish itself. Unfortunately, snuffing had to be done every few minutes. The plated wick, developed in 1820, was an improvement in that it would not roll onto itself as the wick burned, snuffing itself out. This ended the constant snuffing.

After 1859, paraffin candles and kerosene oil lamps were the most popular lighting sources and fuel types used in homes until the 20th century. During the 20th century, these became replaced by gas lighting and electricity. These marvelous innovations decreased family intimacy once found around the candle-lit table of the 19th-century Washington homes.